Can Telling a Story Change the Story?

Leer en español

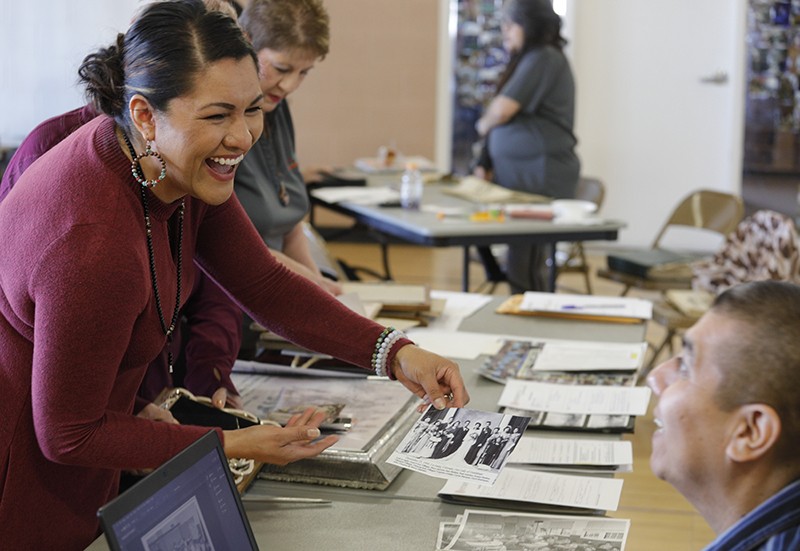

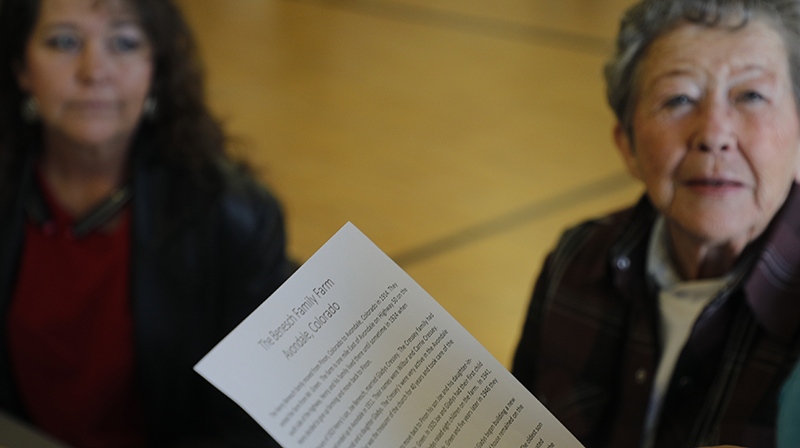

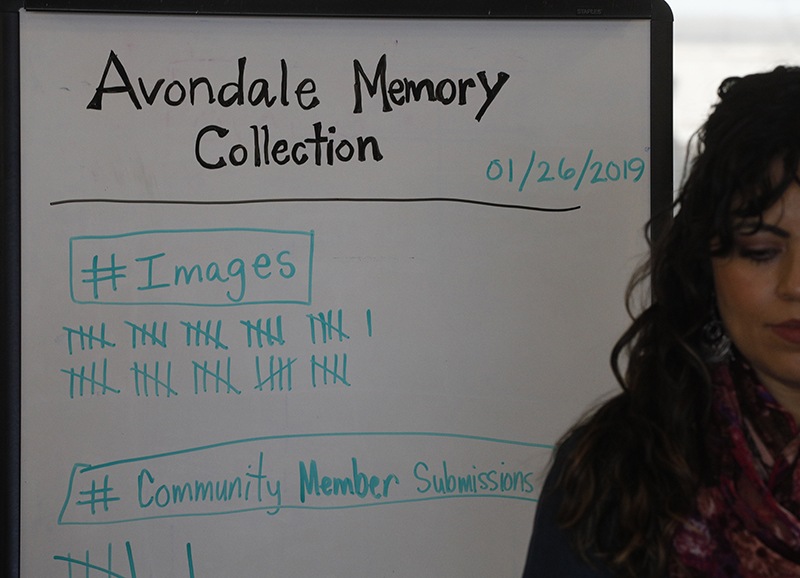

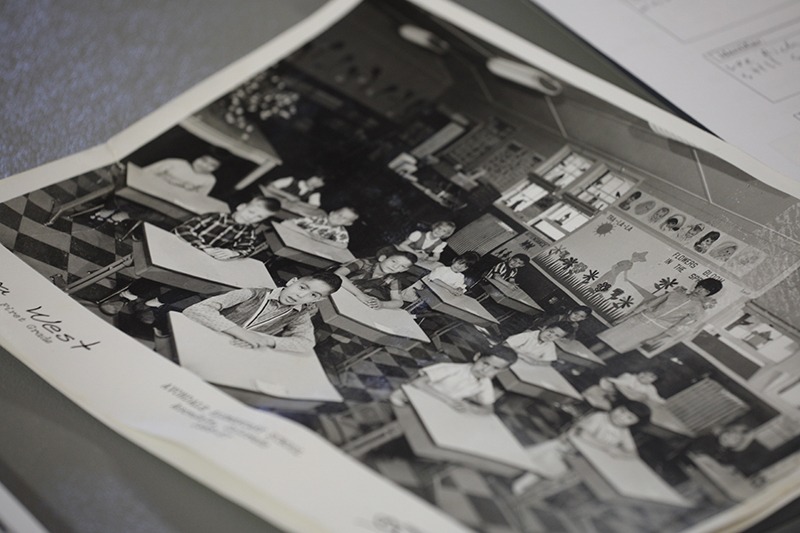

Current and former residents of Avondale, Colo., came together to share photos and tell stories as part of a community memory project with El Pueblo History Museum on Jan. 26, 2019. Photos by Joe Mahoney / Special to The Colorado Trust

By Kristin Jones

When the Colorado Department of Transportation first floated the idea of expanding I-25 through the Eilers neighborhood in Pueblo in 2002, at the cost of bulldozing several dozen houses, there was little organized resistance.

The neighborhood was a historically working-class neighborhood that grew up around two big local employers (and polluters): the smelter and the steel mill. Many of the surrounding mid-century houses were owned and occupied by related families who had fond memories of the church, school and bar that formed the trinity at the soul of the community. They called it Bojon Town; “Bojon” is a slang word for Slovenian, reflecting the immigrant heritage of many of the families there.

But the neighborhood was isolated from other parts of town by industrial development and I-25, had suffered economically from the decline of the steel mill, and was prone to being overlooked by outsiders.

Joe Kocman, whose family has owned the Eilers’ Place bar for several generations, and his wife Pam were hardly thinking of starting a grassroots movement for the preservation of Bojon Town when they reached out to the city. They just wanted a permit to build a garage at their house.

But the planner that showed up, Wade Broadhead, ended up taking an interest in the unique history of the place. With an eye toward a possible historical district designation, Bojon Town residents took part in a survey of the neighborhood in 2009—not just its architecture, but the stories of the people living there, too. The food, the weddings, the music.

That, in turn, invited the attention of a local writer, Dawn DiPrince, who had family roots in the area and wanted to save it from being disrupted or destroyed. She organized events for the community to come together and remember the past—“a collective remembering” she calls it, followed by the collection of oral histories, and then the creation of a piece of art to preserve the neighborhood’s legacy.

The collective remembering was “just amazing,” said Pam Kocman. “I’ll remember it my whole entire life. Everybody knew everybody. What started happening was one person would read their memory, and another person would chime in with another story that went along with that memory.”

In the end, the neighborhood had not just a written history of their community, but a trove of oral histories, a video, and even a song, which was performed for an overflowing crowd at the library.

DiPrince said the finished product didn’t end up serving the purpose she had imagined.

“I had this kind of Pollyanna idea of ‘Let’s create a history of the neighborhood and demonstrate that this neighborhood has value, even though the real estate isn’t as valuable as they’ve seen in the past,’” said DiPrince.

It didn’t quite pan out that way.

“Something even better happened. The neighborhood, in telling their stories collectively and remembering those things—it rekindled their affection for the neighborhood. They became organized. They became activated,” said DiPrince. “The neighborhood came to be seen as a force to be reckoned with.”

The Kocmans and others formed the Eilers Heights Neighborhood Association. Together, they fought the highway expansion, and wrangled with the federal Environmental Protection Agency over what they saw as another potential threat to the neighborhood: its designation in 2014 as a Superfund site. The neighborhood came together to demand that the Superfund cleanup be completed quickly and leave the community in better shape than it was before.

Storytelling as activism

The storytelling initiative ended up being the first of several community memory projects that El Pueblo History Museum has conducted with the leadership of DiPrince, now the chief community museum officer for History Colorado.

The effort has expanded to Denver, where Marissa Volpe of History Colorado has led an effort to collect stories in the Globeville and Elyria Swansea neighborhoods—another Superfund site with a strong sense of community, also fighting against the destructive expansion of a large highway system.

It is part of the history museum’s efforts to include more voices and more perspectives in the history of the state.

Telling stories, said DiPrince, can be a precursor to community activism, as it was in the Eilers neighborhood.

“If people are made to feel like their neighborhoods are a throwaway place, it becomes much easier for systems to throw their neighborhoods away,” says DiPrince. “This storytelling allows people to resist that narrative that they aren’t good enough.”

Storytelling can also be an outcome of activism.

The community of Avondale is about a 20-minute drive east of Pueblo, in a formerly agricultural area, later home to many employees at the Pueblo Army Depot, before it was decommissioned. A rotating team of residents has been working for years to achieve their vision for the community’s future, with support from The Colorado Trust’s Community Partnerships grantmaking strategy.

Part of Avondale’s plan includes recording the community’s history, with the help of El Pueblo History Museum. That work began with an event that asked residents to remember the houses they grew up in, and the things that happened in those houses.

It continued last month with an event that invited residents—and former residents—to bring in their old photographs.

Back in time together

On a clear Saturday, the first Avondale residents arrived at 10 a.m. with folders full of photos. The flyer had said to limit offerings to 10 photos, but a lot of people brought many more than that. A retired teacher brought posters she’d made recording Avondale’s history, going back to the early 20th century. Some people brought albums.

The line to scan photos got backed up, but nobody seemed to be complaining. The photos had sparked questions and conversations. Was it the 1970s or the 1990s when Avondale first got sidewalks? When was the last time we got the whole family together? Where was 19th century trader and pioneer Charles Autobees from, exactly? And who’s the kid in this photo?

Dianna Aragon had brought photos and newspaper clippings of her husband Dan, who died in October. A faded portrait showed him as a handsome 18-year-old in an Army uniform; there were photos of him with their kids; and news clippings of the veterans’ parade he organized as president of the Avondale-Boone Pueblo County Veterans Foundation.

The parade didn’t happen last year, because he was sick. “My hope is that someone will keep it going,” said Aragon.

Rosemary Aldred, who is 90, had a 1920 photo of the Taylor Mercantile Co., which her father opened with support from his family in England.

“I grew up working in the store,” she told a small group that had gathered to admire her collection. She remembered, too, how Avondale got its name: One of its pioneering founders, Sam Taylor, was from a part of England where the River Avon flowed.

Ray Martino brought a photo of his wife Lauri as a 19-year-old, leading a horse through water. They raised their three kids here.

“We love it here. We couldn’t live in town,” said Martino, referring to Pueblo. He was glad to report that one of his daughters, Amie, was moving here with her husband and daughter, and building a house on the family homestead. “They’ll only be a mile away.”

A vision for the future

Avondale has struggled to keep its young families here lately.

“When we had the depot here, we had businesses, restaurants, gas stations. Three little bars. We don’t even have a grocery store. We have older people that can’t drive anymore and we don’t have a transportation system, so they can’t go to town for a medical appointment,” said Lynn Soto. “It’s sad to see our community like this.”

Soto is now the community coordinator for the group of residents in Avondale who are seeking to bring new life to the town. She said telling stories about the past is an important part of their overall mission, which is to fight a sense that the community has been neglected. Their remedy is to lavish attention on it.

“I would like for people to remember that we were a booming community at one time, and the things that we did have,” said Soto. “I hope that it opens people’s eyes that we can be better than where we were, and offer our kids something so that they could go to college and come back.”

Along with the storytelling project, the group has also supported local organizations that provide activities and services for today’s young families, like the Boys & Girls Clubs of Pueblo County and El Centro de los Pobres, which serves migrant workers. They’ve held trainings to help build the community’s advocacy skills, and ramped up language interpretation efforts aimed at encouraging more ties between English- and Spanish-speaking residents.

Back in Bojon Town, Pam Kocman says the storytelling was key to the neighborhood’s mobilization toward a shared vision.

All the houses in the neighborhood are still standing, and the plan to expand the highway there has been shelved.

And though Bojon Town was focused on remembering its own neighborhood, residents there have found themselves more connected to their neighbors on the other side of the highway, Kocman said. They have an idea for the future, which they have communicated to the city. It involves a walkway that connects the neighborhoods, a path to the Pueblo Riverwalk, and plenty of reminders of the past.

“We’ve been cohesive in moving forward,” she said.

Kocman knows it could have gone another way.

“To be real honest with you, I think we would have been at the mercy of these huge government entities,” she said. “Without a coordinated effort, I think things would have been very different.”