Direct Cash Pilot Projects are Increasing Across Colorado

Leer en español

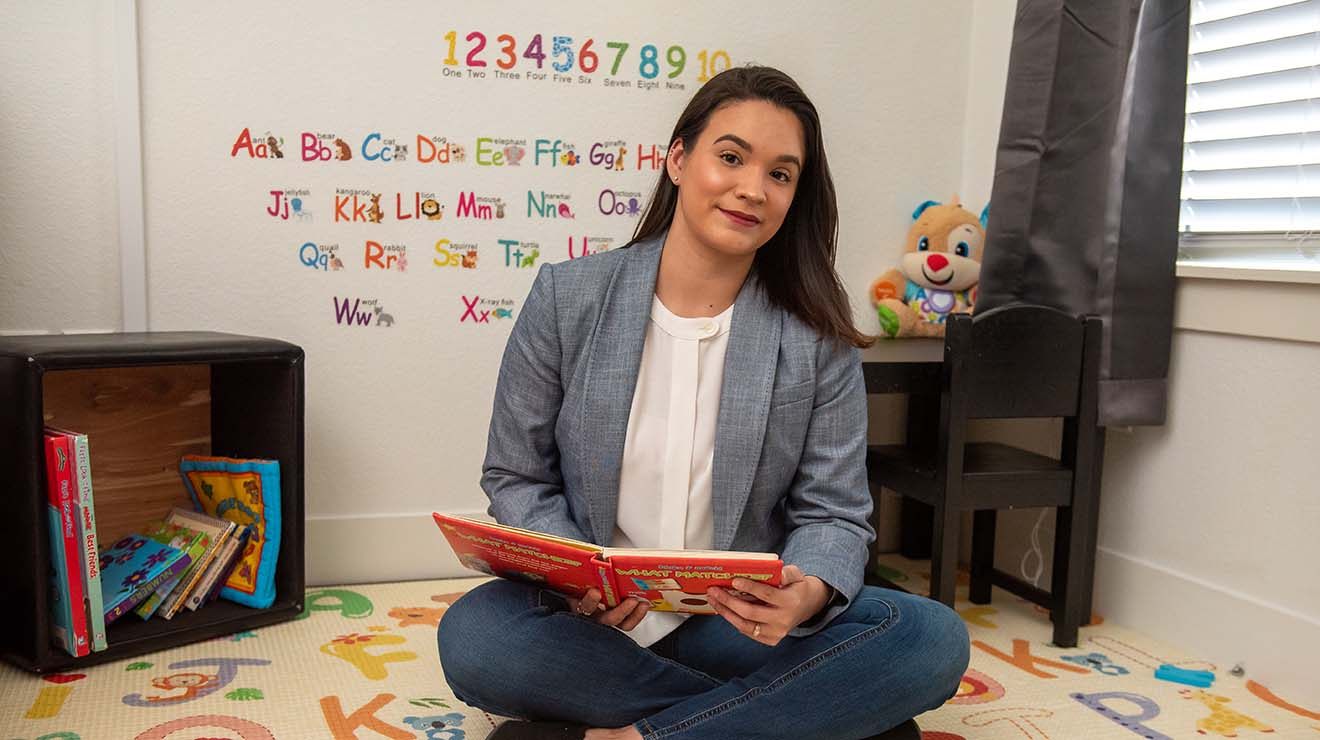

Chrystal Almeida of Thornton, Colo. is one of about 100 people receiving $250 in cash every two weeks as part of a pilot project to help launch home-based child care businesses. Photo by Valerie Mosley / Special to The Colorado Trust

By Jennifer Oldham

Thornton, Colo. resident Chrystal Almeida receives no-strings-attached cash payments every two weeks from one of several national universal income experiments. The money helped Almeida open her own home-based child care business.

Twenty-six year-old Almeida—who lost her job as a medical assistant during the COVID-19 pandemic—bought toys, books and other educational supplies for infants and toddlers with $250 from the Thriving Providers Project that lands in her bank account a couple times per month.

About 100 home-based child care providers like Almeida are participating in the 18-month project as part of a more than $1 million initiative in multiple states spearheaded by Home Grown, a national funders collaborative working to increase access to quality home-based child care. Home Grown partnered with nonprofits in Colorado to raise and distribute money. Almeida can attest demand is high.

“I’ve actually had a lot of people contact me and even text-message me asking if I have availability,” said Almeida, who started caring for two children in November. “I decided to open a day care so I could help other people, stay home with my boys and bring some income to help my husband pay the bills.”

Almeida’s experience echoes that of low-income parents, students, immigrants and others—in cities like Birmingham, Ala.; Des Moines; Tacoma, Wash.; Newark, N.J.; and San Antonio—who received money through one of 100 guaranteed income projects conducted nationwide since 2019.

The philosophy underlying each pilot is simple and powerful: Give people cash and trust them to spend it on things they need. Early results are dispelling long-held misperceptions of why people are living in poverty and what can help lift them out of it.

About 7,337 direct cash pilot participants spent 42% of the money on retail sales and services, 28% on food, and the rest on transportation, housing and other expenses, according to data collected by the Center for Guaranteed Income Research, Stanford Basic Income Lab and Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.

Evidence presented on the partnership’s dashboard, released in September 2022, joins research that found Americans used $850 billion distributed by the federal government early in the pandemic to cover basic needs and business expenses. The nonprofit Economic Security Project declared April 2020 to April 2021 “The Year of Checks,” in which “cash broke through as smart policy and winning politics.”

The unprecedented stimulus effort included the bipartisan expansion of the Child Tax Credit through the American Rescue Plan. Families with children received up to $3,600 per child, depending on their income, in monthly installments from July to December 2021 and as a lump sum tax credit this spring.

The expansion reached 61 million children and became the largest direct cash experiment in U.S. history. It reduced child poverty to its lowest level on record without any impact on parental employment, according to a Columbia University study released in November. (Most of these gains were reversed after the program expired.)

“In 2021, 90% of families received a check per kid per month. For a period of time, the whole nation experienced what it meant to receive a guaranteed income,” said Natalie Foster, president of the Economic Security Project. “It meant the ability to have room to breathe—this is what families that experience guaranteed income pilots are feeling.”

Colorado a trailblazer

The direct cash (used mostly interchangeably with “guaranteed income” or “basic income”) movement exploded after about 100 entrepreneurs, researchers and activists endorsed the Economic Security Project in 2016. The nonprofit went on to help create Mayors for a Guaranteed Income in 2020 with former Stockton, Calif. Mayor Michael D. Tubbs.

In two years, Mayors for a Guaranteed Income grew to include 82 mayors (including Denver Mayor Michael Hancock) who represent more than 26 million Americans, according to the nonprofit’s 2021-22 review. It has tracked about $200 million in direct, unconditional cash assistance flowing to participants between pilots that already started and those in the planning stages.

“I don’t think we could have imagined we would be where we are now three or four years ago,” said Sean Kline, associate director of the Stanford Basic Income Lab. The direct cash movement has “certainly gone a long ways to move those who were skeptical or unaware to become warmer to the idea of direct cash, regardless of political persuasion,” he added.

Colorado is considered a trailblazer in the accelerating movement to expand guaranteed income pilots into nationwide policy. U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet spearheaded the child tax credit expansion effort. U.S. Rep. Jason Crow is among 51 members of the New Democrat Coalition who signed an Oct. 27, 2022 letter urging the lame-duck Congress to extend the program.

Some Republicans are opposed to these efforts. U.S. Sens. Marco Rubio (FL) and Mike Lee (UT) said in a 2021 statement that they did not support turning the Child Tax Credit into a “‘child allowance,’ paid out as a universal basic income to all parents. That is not tax relief for working parents; it is welfare assistance.” All three of Colorado’s Republican U.S. House members voted against the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, which included an expansion of the child tax credit.

An expanded credit failed to make it into a spending package approved by Congress as the session drew to a close last year.

Dozens of Colorado nonprofits aren’t waiting for federal action, and the direct cash movement here is broader and deeper than previously reported. For example, The Women’s Foundation of Colorado’s WINcome program is now reaching residents in more than half of the state’s counties. Additionally, about 50 organizations are part of the newly formed Direct Cash Transfer Community of Practice, which meets virtually to share best practices.

“There are gaps that need to be filled—this is not an individual failing, but a failing of our systems,” said Louise Myrland, vice president of programs at The Women’s Foundation of Colorado. “Diapers and other essential items can’t be purchased with many of the publicly supported resource programs like SNAP—this doesn’t consider the realities of many women and families.”

The Women’s Foundation of Colorado provided 19 direct service organizations with about $1 million in 2021 to dole out as direct cash assistance to women and nonbinary community members. Participants used the money to start new businesses, fund construction apprenticeship programs, or pay fees to complete the immigration process, Myrland said. The program will extend through 2025.

Through its Left Behind Workers Fund, Impact Charitable distributed $38 million in cash assistance to 25,000 households in which workers didn’t receive unemployment benefits during the pandemic, often because of immigration status. (The Colorado Trust provided a $1 million grant to Impact Charitable to support this effort.) The nonprofit sent one-time $1,000 checks to families chosen by community-based organizations who had relationships with the recipients.

“The people who received the cash on average supported three other people with that money,” said Jourdan McGinn, Impact Charitable’s director of economic mobility and direct cash assistance. She added that the nonprofit is preparing to implement additional programs over the next year, as well as to consult on others.

Denver’s basic income experiment

Such direct cash pilot programs are designed to help nonprofits figure out how to most efficiently provide payments to recipients and what dollar amount is best to help improve their economic circumstances. Perhaps no such experiment is as eagerly anticipated as the Denver Basic Income Project, which recently started distributing cash to 700 unhoused people. (The organization has received $500,000 in Colorado Trust funding.)

The pilot, one of the largest direct cash projects to date in the U.S., will give money to three groups of recipients over the next year. One will receive $6,500 up front and $500 a month; a second group will receive $1,000 per month; and a third will receive $50 per month. It ultimately hopes to raise $9 million and serve 820 people.

Nearly 20 community-based organizations helped recruit participants, who must be over 18 years of age. Funds will be transferred to recipients’ bank accounts or provided on a cash card. Impact Charitable’s McGinn is helping manage the project.

The City and County of Denver contributed $2 million through a contract with Impact Charitable to provide cash assistance to 140 women, transgender and gender-nonconforming people. The larger Denver Basic Income Project program is open to all unhoused people, said Mark Donovan, an entrepreneur who conceived the pilot in 2020.

If they agree, participants will be asked to complete biweekly text surveys about their health and financial well-being and housing stability. University of Denver researchers, who will collect and analyze the results, wrote in October that the program will be considered a success if in 2023 recipients are “more securely housed and experiencing improved outcomes,” compared to those who didn’t receive the money.

Rolling out a large-scale pilot to serve a population without stable housing proved challenging. Several early participants in a coalition convened to design the pilot expressed concern about a lack of diversity in decision-making and legal language in paperwork that unhoused residents would be asked to sign prior to participating.

Denver Homeless Out Loud, a nonprofit that advocates for people experiencing homelessness, joined the coalition in 2021 to help it figure out how to best serve the transient community, said Benjamin Dunning, an organizer who observed the process so he could report back to the group’s members. The organization decided to stop participating in the coalition when it felt its concerns weren’t being recognized, he said.

These issues prompted the project to take a step back and hire consultant Mission Spark to ensure that the pilot’s design was inclusive and reflected diverse viewpoints, Donovan said. The program conducted two soft launches to address concerns that arose during the planning phase, he added.

Donovan said that as of Dec. 15, 2022, his group had provided $1 million to 700 unhoused individuals. Anecdotally, the program is already helping. Several people who participated in the soft launches are already off the streets.

“Four payments have already gone out as part of a soft launch that started in July and involved 28 people,” Donovan said in October. “A couple people got housed right away and that was exciting, and surprising.”

Donovan theorized recipients may have used the funds to put a deposit down on an apartment. The University of Denver’s research will help put a finer point on this.

Policymakers nationwide are waiting. They hope results from the pilot will help answer questions that have long stymied direct cash proponents, like whether it’s more helpful to provide participants with cash in one lump sum or monthly.

“The Denver project is a good example of an innovative design that actually is going to teach us something very interesting,” said Stephen Nunez, a researcher at the New York City-based Jain Family Institute, which creates research and pilot designs for direct cash projects.

“Denver folks are not just going to see what happens if we give people money—because we know what happens, they are going to be much better off,” he added. “The question is how much better off and how much money do they need, and what’s the best way to deliver it.”

The project builds on previous efforts like the New Leaf Project in Canada, which distributed one-time payments of $7,500 to 50 unhoused people in 2018 and followed them for a year to determine the impact. The nonprofit found the cash helped recipients move into stable housing more quickly and achieve greater food security.

The Denver project also mirrors research methods employed by the groundbreaking Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, or SEED, which gave $500 per month for two years to 125 randomly selected residents starting in February 2019. Preliminary results show the pilot enabled recipients to find full-time jobs, enhanced their well-being and emboldened them to go back to school.

What these projects didn’t do: Lead to an increase in drug and alcohol usage among participants, or deter them from seeking work. The SEED pilot found less than 1% of the tracked purchases were for tobacco and alcohol. Pilots nationwide catalogued similar results.

Direct cash advocates say they’ve repeatedly disproved these misperceptions and are now focused on collating evidence from pilots nationwide into a policy platform for legislators.

Impact Charitable’s McGinn is marshaling early findings from the Thriving Providers Project, the program that helped Almeida open her home-based child care business. Monthly surveys show the money is making a difference for Almeida and other participants in the pilot.

Prior to the project, 83% of recipients said they had trouble paying for housing, food or utilities, McGinn said. After just the first cash payment of $250, that number dropped by 20%, she added.

“If you give people cash, they spend money on things that they need,” she said. “It’s an important indicator to show the degree at which cash creates economic stability.”