Racial Disparities Still Seen in Discipline Practices in Denver Public Schools

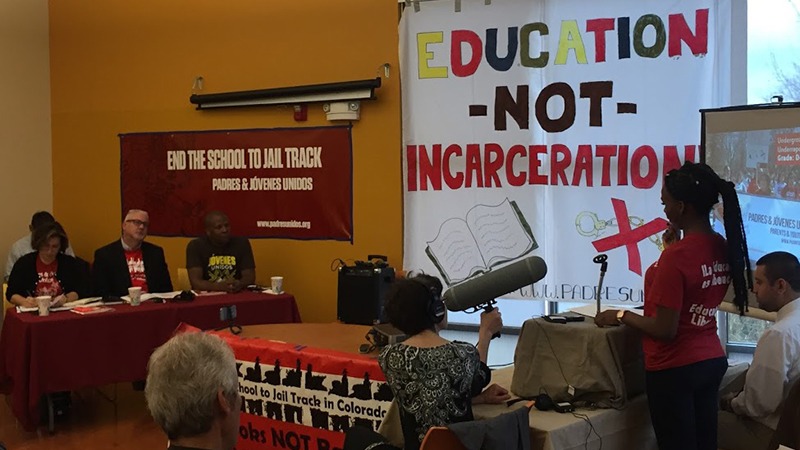

North High School student Jaquikeyah Fields, a Padres & Jóvenes Unidos youth leader, describes her concerns with racial disparities in school discipline numbers to Denver Public Schools officials. Photo by Jaclyn Zubrzycki

By Jaclyn Zubryzcki

When Arianna Peara was in middle school, she was in trouble so often that she recalls her principal setting aside a special area for her in the school’s office.

Now a sophomore at North High School, Peara describes herself as “pre-film director, not pre-prison.”

But Peara, who is Latina, is not alone in having spent significant time outside of class due to teachers’ use of disciplinary measures during her tenure at Denver Public Schools.

During the 2014-15 school year, fewer Denver students were suspended or expelled, and fewer were referred to law enforcement in school, than in any of the past five years. But students of color were more than three times as likely to be suspended or expelled as their white peers, according to a new report from Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, a Denver-based advocacy group that focuses on educational equity and social justice, and a grantee of The Colorado Trust.

Padres & Jóvenes Unidos released its fifth annual report card on school discipline in Denver’s public schools at an event on April 11 that celebrated declining suspension and expulsion rates, but also highlighted stories of parents and students, mostly Latino, still struggling in local schools.

“We have gotten to a level of trust and commitment to change and improve,” said Ricardo Martinez, Padres & Jóvenes Unidos’ executive director. “But the root of problems and disparities is racism, and we don’t want to shy away from that conversation. It’s a legacy that’s still alive and kicking.”

“We know we have significant work to do, but we’ve come a long way,” said Susana Cordova, the district’s acting superintendent. Schools must work with families and other community organizations to understand and respond to the factors that lead to student misbehavior and harsh disciplinary consequences, she said. “We can’t do this alone.”

In 2010-11, the first year Padres & Jóvenes Unidos issued its report card, 7,766 students were given an in-school suspension, 8,892 were given an out-of-school suspension, and 105 students were expelled.

By 2014-15, all three figures were significantly lower, even though Denver Public Schools enrolled more students: 3,776 students were suspended in school, 5,356 were suspended out of school, and 55 were expelled.

Despite that change, racial disparities have persisted. For instance, 1.6 in 100 white students received an in-school suspension last year, compared to 7.9 in 100 black students, 4.5 Latino students, 4.1 Native American students and 1.3 Asian students. In each of the past five years, students of color (defined as all students who are not white, including biracial and multiracial students) have been close to or more than three times as likely to be expelled or suspended.

Some schools are also significantly more likely to take strict disciplinary action than others: For instance, 121 schools did not refer a single student to law enforcement in 2014-15, while a single school referred 53 students.

Denver is not alone in grappling with how to respond when students misbehave, and in attempting to address disparities in how punishments are meted out. A 2014 report from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights found that across the country, students of color are more likely to be suspended or expelled from school—and that such disparities started in preschool. Advocates warn that the impact of school disciplinary decisions can extend well beyond the school day, impacting students’ likelihood of graduating or their ability to get into college or get jobs.

In 2005, Padres & Jóvenes Unidos and national civil rights organization The Advancement Project released a report called Education on Lockdown: The Schoolhouse to Jailhouse Track that highlighted racial disparities in Denver schools. In 2008, the district’s board passed a new school discipline policy that aimed to make sure students’ offenses got proper responses. And in 2013, the district signed an agreement with the Denver Police Department, clarifying that police should only be involved in events in schools that are criminal offenses—such as when a student brings a weapon to school—and not those that are merely disciplinary infractions like lateness or failure to wear a uniform. The city’s ongoing efforts have been held up as a national model.

Still, teachers and students in some schools have reported that they don’t always have the support they need to successfully manage misbehavior, especially since schools are under pressure to keep their numbers of suspensions and expulsions down. A representative for the Denver Classroom Teachers Association said at the Padres & Jóvenes Unidos event that teachers still need more support and training in restorative practices, an approach that aims to thoughtfully address students’ actions in the classroom, especially since many teachers are new to the profession.

At the April 11 event, parents shared stories of discipline gone wrong: A four-year-old suspended for refusing to clean up toys, a Spanish-speaking parent who received a note about her child’s suspension in English, discipline issues that were never properly documented.

In the five years since Padres & Jóvenes Unidos issued the first report card, its focus has broadened from asking for schools to track data on suspension and expulsion to addressing more nuanced questions about what’s actually happening in schools. This year’s report, for instance, notes that some schools may not accurately report suspension and expulsion figures, and that some students are pushed into transferring to alternative schools rather than officially expelled.

Padres & Jóvenes Unidos is calling for Denver Public Schools to focus on making sure that schools accurately report discipline incidents; that teachers are trained in how to manage and deal with student behaviors; that the very youngest students aren’t suspended or expelled; and that parents and students are informed of their rights and the discipline policies that affect them. It also recommends that the district improve data reporting on police involvement in schools and create a coordinated system for responding to complaints about discipline.

“We’re not trying to change student behavior—we’re trying to change adult behavior,” Martinez said.

Meanwhile, the data-focused district is asking for clearer information from Padres & Jóvenes Unidos about what, exactly, would earn the district an A on its report card. (The organization awarded Denver Public Schools a C+, up from a C last year, but there’s no clear rubric for just what metrics will lead the district to a certain grade; for example, the number of suspensions or expulsions that would earn a B compared to a B+.)

At the event marking the release of the report, Cordova signed a statement saying the district would commit to working toward the solutions proposed by the watchdog group.

As for Peara, she said it was nerve-wracking to share her story. In middle school, she was often angry.

But now, she said, she wants to break down stereotypes and encourage more restorative approaches to discipline. “It’s a story that can help other people, so I want to tell it.”