Collaboration Increases Inclusiveness, Depth of Health Equity Report

Leer en español

Organizations working directly with communities in Colorado helped tell the stories of health disparities. Photos by Jaclyn Zubrzycki via the Colorado Center for Law & Policy

By Anna Boiko-Weyrauch

Some Colorado health advocates tread the polished floors of the state capitol and crunch U.S. Census data, while others make neighborhood streets their workplace.

They are two separate, but interconnected worlds.

“We recognize we don’t always have a direct sense of what’s going on in communities,” said Michelle Webster, manager of research and policy analysis for the Colorado Center on Law & Policy (CCLP).

For the past two years, 18 nonprofit organizations have convened quarterly as a cohort as part of The Colorado Trust’s Health Equity Advocacy Strategy (HEAS), to build connections between these different spheres of work. The grantees collectively decide which policy topics to address; which capacities to build and strengthen; and how program funds should be used.

The belief that it is more effective and sustainable for a field of advocates to work together to address health equity-related policy issues—rather than the same organizations working on health equity in silos—is also known as “field building.”

As a result, Webster and CCLP are benefiting from the expertise of their counterparts across the field of health advocacy to deepen and enrich their research.

The most recent example is the new CCLP report, Vital Signs: The Influence of Race, Place, and Income on Colorado’s Health, which details how profoundly these social determinants and others can determine the health of Coloradans.

The health equity advocacy meetings influenced the focus of the report before it was even written. Specifically emphasizing race in the report was a way for CCLP to honor the cohort’s shared commitment to dismantling the health impacts of racial disparities, Webster said.

Additionally, the cohort established inclusivity of the voices of affected communities as a major value, which also influenced the report’s content.

The report includes four stories of people and community organizations grappling with health challenges, namely Re:Vision’s community garden for low-income neighborhoods, Asian Pacific Development Center’s mental health care services for refugees, Grand County Rural Health Network’s programs increasing health care accessibility for rural Coloradans, and Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition’s advocacy and assistance for people living with disabilities and their caregivers.

Webster got ideas for analyzing the data in new ways by being part of the cohort. Past CCLP research has examined income and race separately from each other; Webster wondered, why not combine the variables?

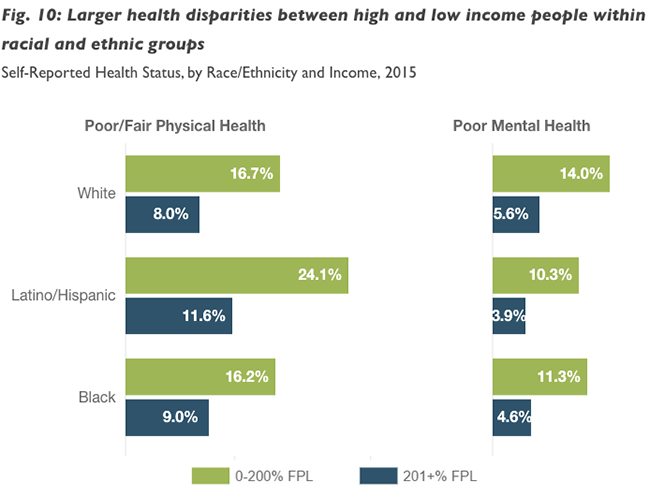

The result (below) shows health gaps are larger in Colorado between income groups within the same race or ethnicity than between racial or ethnic groups.

Source: Colorado Health Access Survey 2015

Varied members of the HEAS cohort—namely the Colorado Children’s Campaign, FRESC: Good Jobs Strong Communities, Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, and Lake County Build a Generation reviewed an early draft of the report and its website before it went live.

“Just sort of a gut-check on, ‘does this sound right?’” Webster said. “‘Are we telling the story that needs to be told here?’”

In a later conference call to review the report, FRESC policy analyst Quinn Williams recommended capitalizing the first letter of all racial and ethnic groups; not only Latino and Asian, for example, but Black and White, too. The words represent cultural identities and should be treated like proper nouns, Williams said. The final report did just that.

The conversations around the report helped the organizations assure as many different voices as possible were represented in the final product, Williams said—achieving one of the key ongoing goals of the HEAS collaboration.

“I’m feeling like our thoughts were genuinely included,” he said.

Cohort members will be able to use the report to inform their advocacy, and Williams said the report gives FRESC’s community organizers more to talk about in the community.

Additionally, CCLP will convey the health equity information in the report to lawmakers through the organization’s legislative testimony and one-on-one meetings.

Legislators are always looking for specific data to justify funding decisions, so revealing county-level health disparities can be very persuasive, Webster said.