Racism Hurts All of Us

Leer en español

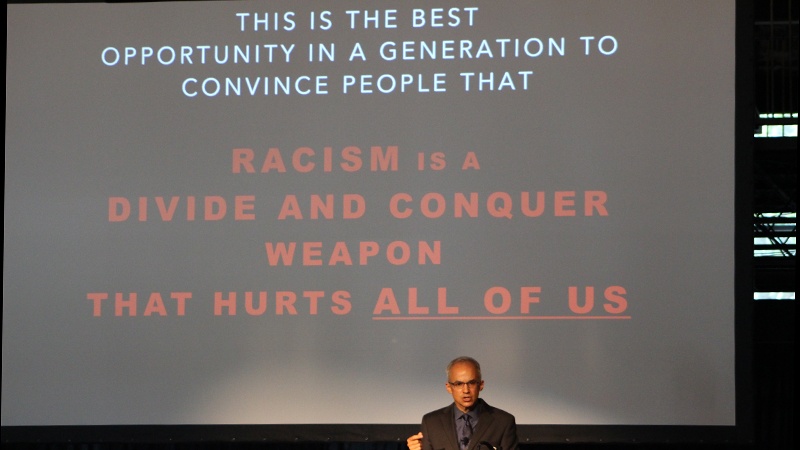

Ian Haney López spoke to an audience in Denver in early May as part of The Trust’s Health Equity Learning Series. Photo by Rachel Mondragon

By Kristin Jones and Ned Calonge, MD, MPH

In 1964, when Lyndon B. Johnson was campaigning for president, he proposed ending poverty. A goal so audacious is unimaginable in today’s political climate—from politicians on either side of the aisle. And yet Johnson won in a landslide.

It was a time in America’s history when the political consensus from the left and the right was that government should help people. But by the time Johnson won the 1964 presidential election on an anti-poverty platform, the deliberate erosion of that consensus was already underway.

That’s because, around the same time, Republicans spied an opening: the civil rights movement had unearthed racial anxiety and resentment among whites, especially in the solidly Democratic south. Strategists saw a wedge they could use to divide a coalition of white working-class voters and African Americans.

This is the conclusion legal scholar and writer Ian Haney López, the author of Dog Whistle Politics, reached based on his research of U.S. political strategies as they’ve evolved since the Johnson era. His findings and conclusions, presented at Denver’s Mile High Station in early May, are summarized here. Haney López’s presentation will be re-broadcast around the state in viewing parties with facilitated discussions as part of The Trust’s Health Equity Learning Series.

Covering a 1963 meeting in Denver of the Republican National Committee, conservative journalist Robert Novak wrote: “A good many, perhaps a majority of the party’s leadership, envision substantial political gold to be mined in the racial crisis by becoming in fact, though not in name, the White Man’s Party.”

Haney López calls this dog whistle politics: saying in code what was politically unpalatable to say directly—all at the service of a goal of concentrating power and wealth.

Like a dog whistle, the language used by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater and his party signaled at a high frequency for its intended audience, and was silent for others. The “states’ rights” espoused by Goldwater was understood to mean that the federal government couldn’t force schools to integrate. “Freedom of association” was known to mean that restaurants could choose to serve only white patrons.

In his talk, Haney López offered a powerful account of how U.S. politicians in subsequent generations have preyed on racial anxieties to build their own power and shift resources to corporations and the very rich.

Politicians created a new breed of racism when they began to utilize it as a strategy, Haney López said, by building high walls between communities with common interests.

The winners of this strategic racism are few but powerful. The very rich have reaped enormous benefits from the erosion of a consensus that government should advance the interests of the American people. In the past 50 years, said Haney López, coded racial appeals have helped develop a competing consensus: That each of us is on our own, and that the wealthy deserve to be rewarded for their gains.

The losers of this strategy, he said, include all the rest of us, who have increasingly come to accept poverty, ill health and growing inequality as inevitable outgrowths of our so-called meritocracy.

Each political generation has brought a new iteration of dog whistle politics. If Goldwater pioneered the coded racial appeal, Richard Nixon was the first to master it.

“Nixon made a decision that he would go after the racist vote,” said Haney López. In 1972, eight years after Lyndon Johnson won in a landslide, Richard Nixon won in an even bigger landslide.

Campaigning on states’ rights, freedom of association, the bogeyman of “forced busing” (another way of saying integrating schools), and law and order, Nixon brought about a sea change in American voting patterns, said Haney López, that persists today.

“Today’s Republican Party draws roughly 90 percent of its support from white voters,” he said. “The Republican Party today is drawing upon the most racially fearful whites as a strategy. They went and did what they said they were going to do.”

Ronald Reagan’s first presidential campaign stop after winning the Republican Party nomination was in Philadelphia, Mississippi, promising to uphold states’ rights in a place most notable for being the site of the lynching of three civil rights leaders in 1964.

“What Reagan figures out is how to connect dog whistle politics with a hostility towards government,” said Haney López. “And he does it through phrases like ‘welfare queen.’”

Reagan painted a picture of “some young buck” (changed in later iterations to “some young fella”) standing in line in front of you at the grocery store, buying a T-bone steak with food stamps while you’re waiting to buy a hamburger. The coded lesson of this story was the government was taking the hard-earned money of whites, in the form of taxes, and spending it on undeserving minorities.

It worked. Policies that promoted cutting taxes, cutting social spending, and trusting the marketplace and the rich to provide economic prosperity gained solid ground—and not only among Republicans.

“Starting in the ‘90s, the Democrats start to dog whistle, too,” said Haney López. “You get an active competition between the Republicans and the Democrats to appeal to racially resentful whites, by this sort of upward bidding to prove which party is tougher on people of color.”

President Clinton’s attacks on welfare, and his pursuit of tough-on-crime policies that resulted in the incarceration of millions of black and brown Americans, were driven by this competition, said Haney López.

After 9/11, a new racial bogeyman emerged in the form of Muslims. At the same time, efforts to exploit whites’ racial anxieties expanded to demonizing Latinos, especially undocumented immigrants.

President Trump’s campaign rhetoric of banning Muslims and building a wall along the border with Mexico, said Haney López, drew directly on a strong tradition of appealing to racial fears—once again in support of policies that concentrate wealth at the expense of everyone else.

And the country’s increasingly concentrated wealth in the hands of a few is truly something to fear, said Haney López: “Concentrated wealth is dangerous. It erodes social bonds. It ends up using its power to take more and more wealth and power for itself.”

The solution, he said, lies in recognizing our shared humanity and fighting concentrated wealth. That means demanding that government serve us all, by promoting our shared economic prosperity and our flourishing as humans. It means trusting each other.

“People voting their racial fears are doing tremendous damage to themselves,” said Haney López. “This is really the best opportunity, maybe in the history of the country, to really say to whites, ‘you have more to lose than gain from racism.’ Racism is a divide-and-conquer weapon that hurts all of us.”

Haney López’s entire talk is available for download as a podcast and video.