Want to Build Power? Make a Friend

Leer en español

Heather Nielson outside the office of The Community Voice, which has brought together community members in Dove Creek. Photos by Kristin Jones

By Kristin Jones

DOVE CREEK, COLO.—Sometimes, living in a small town inspires enduring friendships. And sometimes it doesn’t.

Earlier this year, the town council of Dove Creek, a Colorado community of around 700 people just east of the Utah border, sat down with Dolores County commissioners.

This shouldn’t have been a noteworthy occasion. After all, Dove Creek is the county seat of Dolores County.

But it was. The consensus around town is that it’s been 50 years—give or take—since the last time that happened.

“They just didn’t see the need,” said Ronda Lancaster, who works in Dove Creek and lives in nearby Pleasant View. Town and county leadership “were off doing their own thing.”

In fact, she said, “They were doing the same thing and they didn’t know it.”

The meeting came about after a coordinated effort by Dove Creek residents who were looking for ways to improve the health and prosperity of the town, with support from The Colorado Trust’s Community Partnerships strategy.

The group of neighbors, which calls itself The Community Voice, has been meeting for years to get to the root of the biggest challenges here. Around 300 community members have shown up to meetings to discuss the town’s assets and develop solutions for its problems.

Some of the struggles were obvious, and common to a lot of rural America: disappearing jobs, sinking wages and an aging population. Some were particular to Dove Creek. In Wild Coffee, a cozy sandwich and coffee shop in a house near the highway, on a recent September day, three friends talked about the effects of a long-lasting drought here. The farmers here traditionally employ dryland farming techniques—meaning without irrigation—to grow staples like Anasazi and pinto beans. It’s a method that’s uniquely suited to the climate, and vulnerable to changes in the weather.

“If we don’t get blanketed with heavy, wet snow this winter, towns like Dove Creek are just going to disappear,” said Heather Nielson, who lives here and organizes outreach for The Community Voice.

When The Community Voice members turned toward solutions, they found that a lack of collaboration between local organizations was a real barrier to the kind of progress that could revitalize the community, bring in new sources of income to jumpstart the local economy and engage young people.

The town council, the county commissioners, social services, the school district and local nonprofits were all doing good work. They just weren’t doing it together.

Much of The Community Voice’s work so far has been to support and expand (rather than duplicate) the efforts already going on.

“We want to bring the kids together, by giving them things they enjoy doing,” said Lancaster, who was hired by The Community Voice to work as a community coordinator. “We didn’t have the expertise to do it all ourselves.”

Using funds via the Community Partnerships strategy, The Community Voice gave a grant to fix the bathroom in the town’s only day care. They gave money to the local public school to support additional activities for the student council. They funded a new after-school program; school librarian Laurie Ernst suggested it at a teacher appreciation luncheon hosted by The Community Voice, and it’s been an obvious need for years.

At the same time, the resident team gave scholarships to a local online school that’s a low-cost private alternative to the public school—kind of a one-room school house with Wi-Fi. And they gave grants for various programs offered by a local nonprofit called Reaching Out to Community and Kids, which offers summer art classes and emergency food help, among other things.

Kiara Lingenfelter is a junior at Dove Creek High School. She’s happy for opportunities she’s had that The Community Voice supported, including leadership trainings with her fellow student council members, and chances to network with student leaders from other schools. When she thinks about her future, she sees Dove Creek.

“I definitely think Dove Creek is a place that’s worth coming back to,” said Lingenfelter. “I like the school here. My first thought [about the future] is becoming a teacher. The teacher-to-student ratio is so small. I like the relationships you have with teachers here.”

One happy byproduct of The Community Voice’s bringing people together was also more civic engagement. The elections for town council and mayor—long open to whoever would volunteer—suddenly became competitive.

“This is what The Community Voice has done for us. They turn up for every meeting,” says Brett Martin, the newly elected Dove Creek mayor. “I just sit and listen, whether I agree or disagree. It’s a voice of the community that can be represented at the town board level. Dove Creek hasn’t had that in the past.”

By the end of the meeting between the town and the county, they had agreed to share responsibility for hiring a new code enforcement officer. But more importantly, they had made contact, and started building a relationship that has the potential to make a big difference here.

Breaking Through Silos

The tendency for organizations to silo themselves—and sometimes to compete against each other, rather than work together—is hardly unique to rural agencies.

The day after I visited Dove Creek, 100 miles east and a universe away, a caravan of buses were setting out from a hotel in Telluride for a tour of the region. The buses were filled with employees at 33 nonprofits that are engaged in solving tough issues like improving access to housing and health care, strengthening the economy or fighting hunger, among others.

Nonprofits that advocate for similar interests should be natural allies. But it doesn’t always work out that way. Part of the fault lies with philanthropy, which can encourage competition by funding individual nonprofits without regard to the ecosystem that they inhabit. There are few grants that reward cooperation; many do the opposite.

The Trust’s Health Equity Advocacy (HEA) strategy is an effort to fund collaboration among nonprofits and local agencies—including public health agencies, medical service providers, policy advocates and community organizers—that are tackling similar problems from different angles. The Trust funds 18 organizations to work together, in essence. And those organizations have responded not only by throwing themselves into a collaborative effort, but also by asking to expand this group and draw in others.

And so, last month, the van that I rode in included a guide from the Telluride-based Tri-County Health Network, and representatives from organizations as far flung as Denver Health; the Southwest Center for Independence, which has offices in Durango and Cortez; and Lake County Build a Generation, in Leadville. Some of them were among the original 18 Trust grantees in the HEA cohort; others were invited to join as “network-strengthening partners” by those grantee organizations, to share resources and expertise.

The tour came on the second day of a convening that had the purpose, in part, of introducing nonprofits to the challenges and resources in this part of the state—and to find common ground as well as explore differences. In Telluride, the participants had heard from local Latinx leaders who spoke about how hard it is for most people who work in the town to also live there, given the exorbitant housing costs.

Now, the van tours were introducing nonprofits to the towns outside of Telluride, including Norwood, Naturita and Nucla.

Tri-County Health Network, which integrates and improves the quality of health care in the area, works in partnership with a wide array of schools, medical providers and community leaders.

What Friends Are For

During the day, the power and potential of an expanded network of allies became clear, as the organizations learned from each other’s work, asking questions and making connections that drew on their own expertise.

At the food bank at Christ in FOCUS Church in Norwood, Michele Blunt, the food bank coordinator, said a total of around 450 families had benefited from the food here, and the need is increasing. That’s especially significant because fewer than 600 people live in the town; people travel to the food bank from as far away as Dove Creek.

At the food bank at Christ in FOCUS Church in Norwood, Michele Blunt, the food bank coordinator, said a total of around 450 families had benefited from the food here, and the need is increasing. That’s especially significant because fewer than 600 people live in the town; people travel to the food bank from as far away as Dove Creek.

Tara Manthey, who manages communications for the Colorado Children’s Campaign, one of the 18 HEA cohort members, asked Blunt what would make her job easier. Blunt replied that the primary thing she needed was help with the piles of paperwork that each food pickup required.

“All these systems are meant to prevent fraud,” Manthey said later, in the van, reflecting on regulations designed to verify that people receiving food and other government-subsidized services are truly poor. But these systems end up burdening food banks like this one, and the people who work there, with stacks of paperwork, she said.

As a policy advocate, the Children’s Campaign pushes for changes in laws and policies—like those involving food access—that are written at the State Capitol and affect people like Blunt, hundreds of miles away.

At several stops, including the Basin Clinic, a safety-net clinic in Naturita, people mentioned the need for home health services to care for an aging population. Martha Mason asked whether they had thought of making use of a Medicaid waiver that allows family members to provide care for people who are elderly or have disabilities, and be paid for it. Mason is executive director of the Southwest Center for Independence, which is led by people with disabilities and provides support and training for the disability and elder communities in the southwest region of Colorado.

Later that afternoon, the group gathered again for a different activity. This one was aimed at taking stock of the work that each organization had done to promote racial equity—a key goal of the HEA cohort.

Sometimes it takes an outside perspective to hold organizations accountable to their own objectives.

Jose Torres-Vega, a civil rights advocate with the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, another HEA cohort member, expressed frustration that the group was always talking about racial equity, but not doing anything about it.

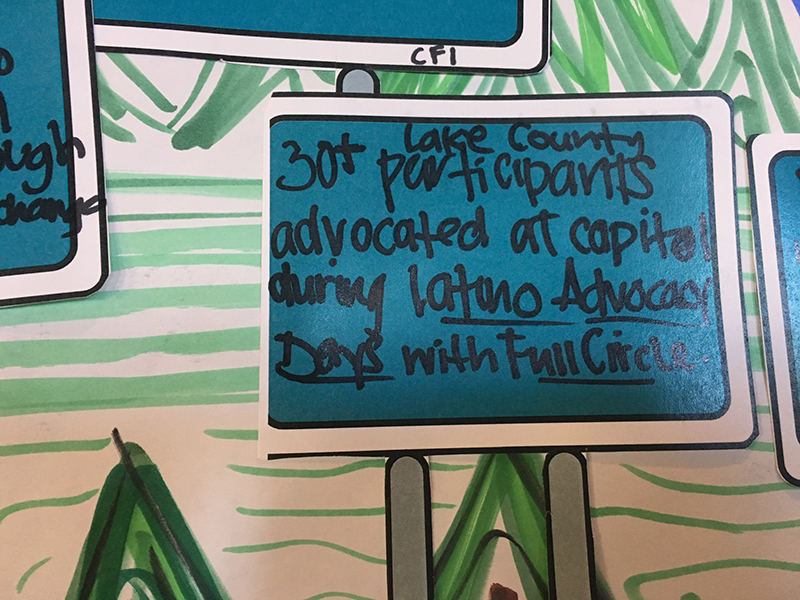

But then the participants listed the things they had done, by organization: Providing simultaneous interpretation at community meetings, hiring more people of color, translating marketing materials into Spanish, traveling to the Capitol to advocate alongside more than 30 Latinx leaders from Lake County, getting a school funding initiative on the ballot. Dozens of things.

“OK,” said Torres-Vega. “I guess we have done a lot.”

That’s another thing friends are good for: Pointing out the progress you’ve already made.

One of many achievements recorded by nonprofits working toward racial equity in Colorado.